Which African countries? What is their population density? Are they 3rd world or do they have sophisticated economies? How much foreign travel do they get?Eastern Oregon Bear said:movielover said:sycasey said:Okay, but if it does then that just means you're likely to get a worse outcome from a Covid infection if you're fat. It doesn't mean that being thin will prevent you from catching Covid. Do you guys even know what you're arguing anymore?movielover said:

No one has studied it. The virus allegedly replicates in fat cells, hence the reason why people obese people were hit harder.

And again, the vaccines are better than anything else at preventing bad outcomes from an

infection.

And you know this how?

Note some African countries with very low vaxx rates also have incredibly low infection rates. Why? We know that there are low obesity rates, plenty of Vitamin D (sun), and Ivermecton for river blindness. I believe one country had less than 5,000 infections, but allegedly wealthy Africans w a western diet (fat) had a much higher infection rate.

Vaccine Redux - Vax up and go to Class

986,984 Views |

6198 Replies |

Last: 6 days ago by sycasey

Eastern Oregon Bear said:Haven't you kept with the literature that says Vitamins C and D, Zinc and Ivermectin prevent hurricanes or at least lessen the effects?sycasey said:Perhaps in your language, this was a withering retort. I'll never know why.Zippergate said:Thanks for that advice. I'll remember it the next time there's a hurricane coming.sycasey said:

If people want to not get vaxxed and take their chances with the virus, then at this point I say, whatever, it's your life.

That wasn't the question I was addressing. It was about what doctors should recommend as the BEST way to avoid bad outcomes if you do catch Covid. That's still the vaccines.

My understanding is that Zinc is typically combined with either Ivermectin or Quercetin (OTC equivalent) for success as a therapeutic. Zinc stops replication of Covid inside the fat cell, while Ivermectin / Quercetin injects the Zinc into the cell.

Florida also implemented other medically proven therapeutics - which were being effective - and then the Biden Administration put up roadblocks.

movielover said:Eastern Oregon Bear said:Haven't you kept with the literature that says Vitamins C and D, Zinc and Ivermectin prevent hurricanes or at least lessen the effects?sycasey said:Perhaps in your language, this was a withering retort. I'll never know why.Zippergate said:Thanks for that advice. I'll remember it the next time there's a hurricane coming.sycasey said:

If people want to not get vaxxed and take their chances with the virus, then at this point I say, whatever, it's your life.

That wasn't the question I was addressing. It was about what doctors should recommend as the BEST way to avoid bad outcomes if you do catch Covid. That's still the vaccines.

My understanding is that Zinc is typically combined with either Ivermectin or Quercetin (OTC equivalent) for success as a therapeutic. Zinc stops replication of Covid inside the fat cell, while Ivermectin / Quercetin injects the Zinc into the cell.

Florida also implemented other medically proven therapeutics - which were being effective - and then the Biden Administration put up roadblocks.

There is a reason Veru's adcom was delayed until November 9, despite this happening on April 11.

"The decision [to stop the phase 3 trial] came unanimously from Veru's independent safety monitoring committee after sabizabulin was found to reduce deaths by 55% compared to placebo among hospitalized patients with moderate to severe COVID"

There is money to be made by the people in power. You can make a ton of money monopolizing expensive covid treatments. Pfizer crushed earnings.

My back of the envelope estimate was potentially $300 B just in the US over a few years?

I've heard a few doctors discuss the lack of motivation to test Vitamin D, Ivermectin, etc. - "reprocessing" known drugs or supplements - and there is no incentive to spend $10 million on a study for something which costs pennies to make and sell.

You'd think our government and 150+ medical universities would do this as a public service. Brave doctors on the ground were doing it. (Some also included steroids in their treatments.) At one point Israel noted through their existing medical database that citizens who were taking low-dose aspirin were less likely to be infected.

These reprocessed drugs or vitamins - we know their potential negative effects are zero, or close to zero. Virtually no risk.

I've heard a few doctors discuss the lack of motivation to test Vitamin D, Ivermectin, etc. - "reprocessing" known drugs or supplements - and there is no incentive to spend $10 million on a study for something which costs pennies to make and sell.

You'd think our government and 150+ medical universities would do this as a public service. Brave doctors on the ground were doing it. (Some also included steroids in their treatments.) At one point Israel noted through their existing medical database that citizens who were taking low-dose aspirin were less likely to be infected.

These reprocessed drugs or vitamins - we know their potential negative effects are zero, or close to zero. Virtually no risk.

Eastern Oregon Bear said:Haven't you kept with the literature that says Vitamins C and D, Zinc and Ivermectin prevent hurricanes or at least lessen the effects?sycasey said:Perhaps in your language, this was a withering retort. I'll never know why.Zippergate said:Thanks for that advice. I'll remember it the next time there's a hurricane coming.sycasey said:

If people want to not get vaxxed and take their chances with the virus, then at this point I say, whatever, it's your life.

That wasn't the question I was addressing. It was about what doctors should recommend as the BEST way to avoid bad outcomes if you do catch Covid. That's still the vaccines.

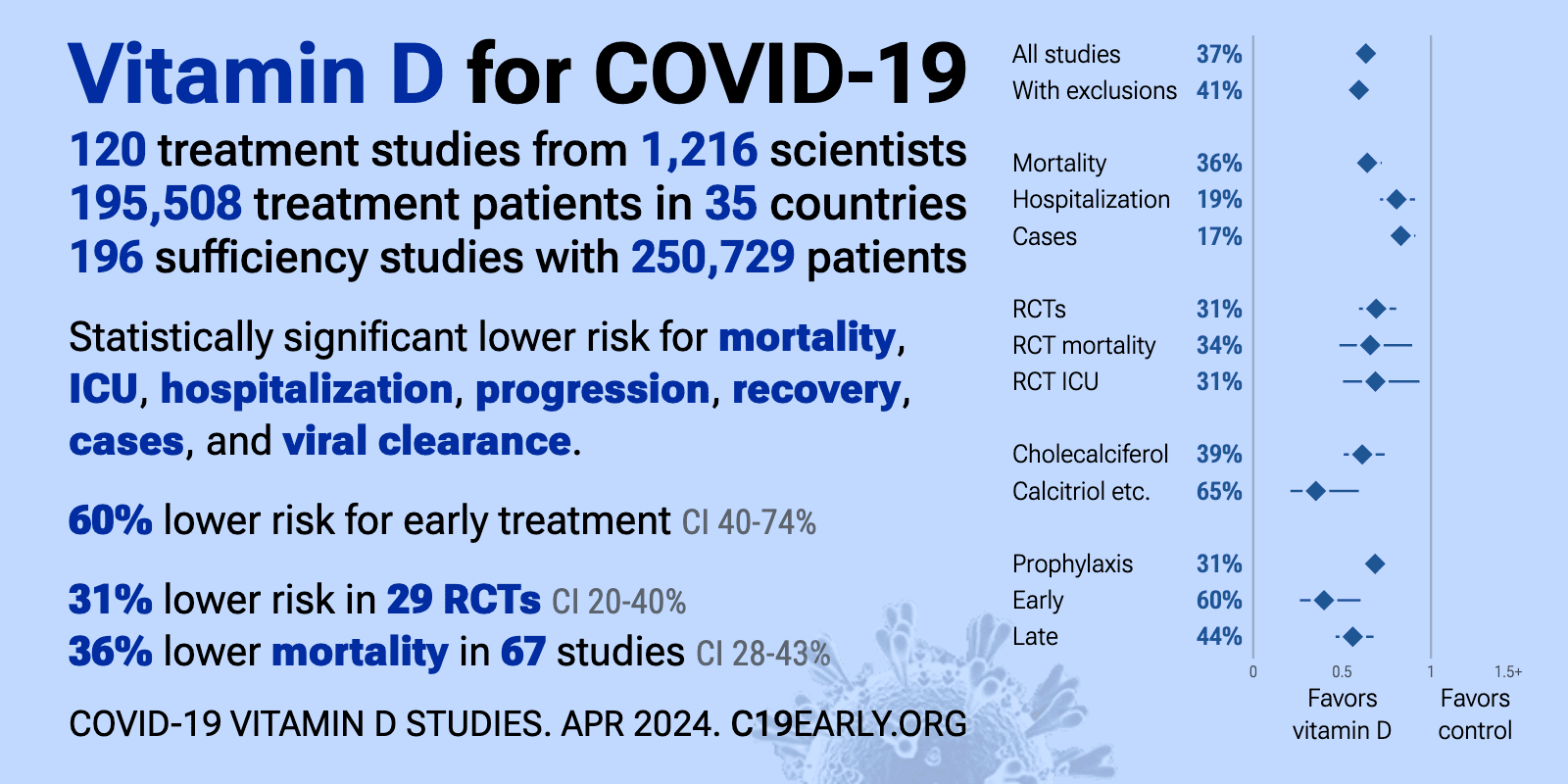

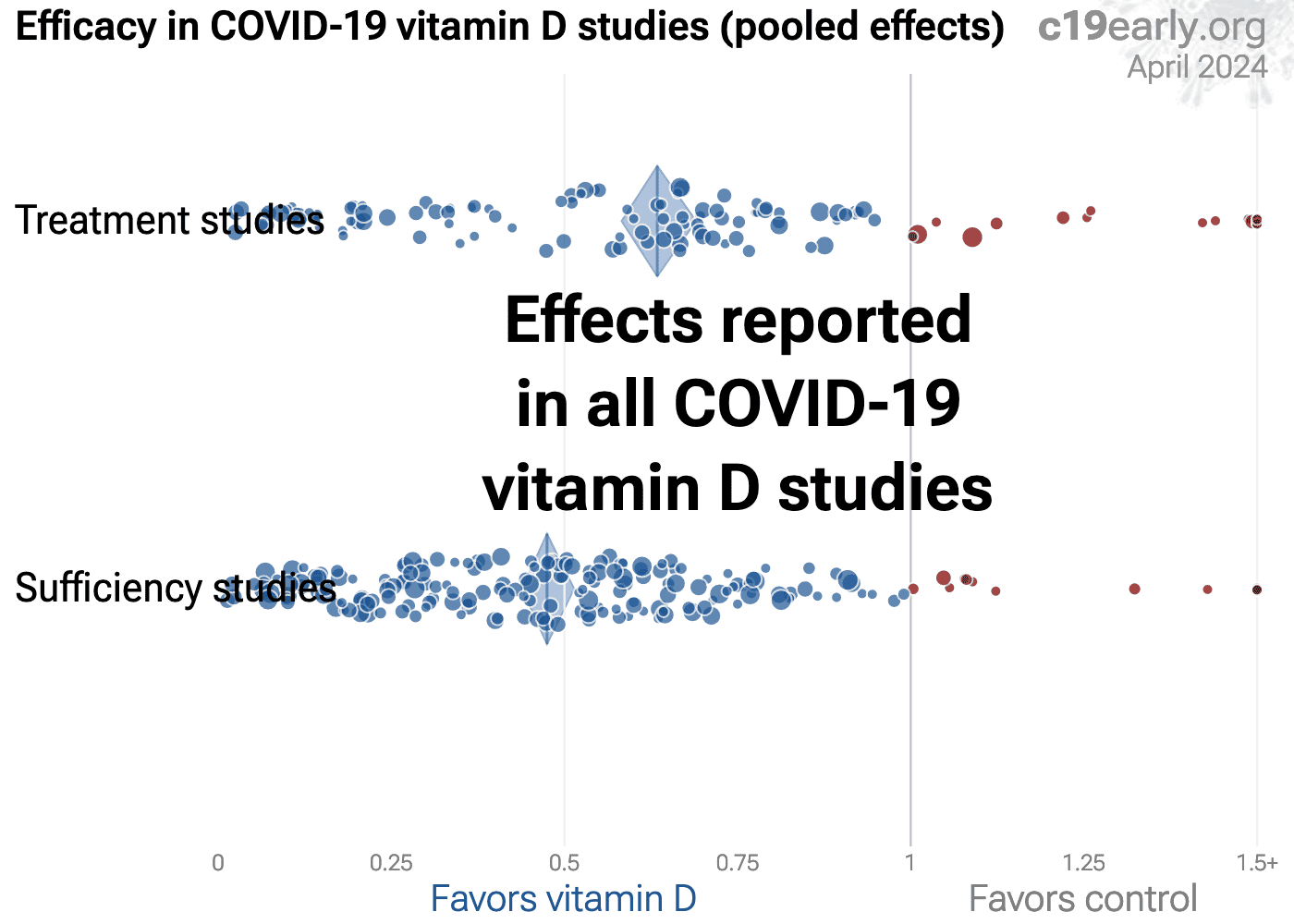

List of new and recent studies on the effects of vitamin D on covid:

https://c19early.org/d

Highlights:

https://c19early.org/dmeta.html

Vitamin D reduces risk for COVID-19 with very high confidence for mortality, ICU admission, hospitalization, recovery, and in pooled analysis, high confidence for cases, and low confidence for ventilation, progression, and viral clearance.

We show traditional outcome specific analyses and combined evidence from all studies, incorporating treatment delay, a primary confounding factor in COVID-19 studies.

Real-time updates and corrections, transparent analysis with all results in the same format, consistent protocol for 47 treatments.

Summary of findings and studies results:

Cal88 said:Eastern Oregon Bear said:Haven't you kept with the literature that says Vitamins C and D, Zinc and Ivermectin prevent hurricanes or at least lessen the effects?sycasey said:Perhaps in your language, this was a withering retort. I'll never know why.Zippergate said:Thanks for that advice. I'll remember it the next time there's a hurricane coming.sycasey said:

If people want to not get vaxxed and take their chances with the virus, then at this point I say, whatever, it's your life.

That wasn't the question I was addressing. It was about what doctors should recommend as the BEST way to avoid bad outcomes if you do catch Covid. That's still the vaccines.

List of new and recent studies on the effects of vitamin D on covid:

https://c19early.org/d

Summary of findings and studies results:

Did we ever mandate Vitamin D? Have there been any vitamin D commercials in the radio? I heard about 5 per day Pfizer covid vaccine commercials on the radio for about a year.

Cal88 said:Eastern Oregon Bear said:Haven't you kept with the literature that says Vitamins C and D, Zinc and Ivermectin prevent hurricanes or at least lessen the effects?sycasey said:Perhaps in your language, this was a withering retort. I'll never know why.Zippergate said:Thanks for that advice. I'll remember it the next time there's a hurricane coming.sycasey said:

If people want to not get vaxxed and take their chances with the virus, then at this point I say, whatever, it's your life.

That wasn't the question I was addressing. It was about what doctors should recommend as the BEST way to avoid bad outcomes if you do catch Covid. That's still the vaccines.

List of new and recent studies on the effects of vitamin D on covid:

https://c19early.org/d

Summary of findings and studies results:

Call88 = mensch

Eastern Oregon Bear = not so much

EOB = doesn't this make you happy?

Never heard one. One of the internists / specialists on the Laura Ingraham program, he was from New Jersey, said that some people are Vitamin D deficient. And for some reason, people with dark pigmentation - African, East Indian - may be more prone to this deficiency.

The non-approved censored doctors were recommending this since the early days.

The non-approved censored doctors were recommending this since the early days.

oski003 said:Cal88 said:Eastern Oregon Bear said:Haven't you kept with the literature that says Vitamins C and D, Zinc and Ivermectin prevent hurricanes or at least lessen the effects?sycasey said:Perhaps in your language, this was a withering retort. I'll never know why.Zippergate said:Thanks for that advice. I'll remember it the next time there's a hurricane coming.sycasey said:

If people want to not get vaxxed and take their chances with the virus, then at this point I say, whatever, it's your life.

That wasn't the question I was addressing. It was about what doctors should recommend as the BEST way to avoid bad outcomes if you do catch Covid. That's still the vaccines.

List of new and recent studies on the effects of vitamin D on covid:

https://c19early.org/d

Summary of findings and studies results:

Did we ever mandate Vitamin D? Have there been any vitamin D commercials in the radio? I heard about 5 per day Pfizer covid vaccine commercials on the radio for about a year.

Lack of vitamin D is one of the main reasons people with darker skin in northern latitudes both in Europe and in N. America had higher covid mortality rates. There aren't a lot of obese Somalis in Sweden, but they came down with covid at much higher rates:

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(21)01339-8/fulltextQuote:

in Sweden, for example, 32% of people testing positive for COVID-19 (from the start of the pandemic to May 7, 2020) were migrants, mainly from Turkey, Ethiopia, and Somalia.

3

In Norway, 42% were migrants, according to the Norwegian COVID-19 national datasets as of April 27, 2020, and the highest proportion of these migrants were born in Somalia.

As well the traditional diet in nordic countries is rich in vitamin D (lox, herring, dairy etc), much more so than that of the migrants.

Are you a vaxx denier? s/

https://newsrescue.com/whys-covid-sparing-africa-japanese-scientists-attempt-to-answer-worlds-trickiest-medical-puzzle/Eastern Oregon Bear said:Just how many people in these African countries are taking Ivermectin to treat River Blindness? I think it would have be 80%-90% or higher to draw a meaningful correlation. If it's just 5%-10%, I doubt if the effects would be more than small blip in the data.movielover said:sycasey said:Okay, but if it does then that just means you're likely to get a worse outcome from a Covid infection if you're fat. It doesn't mean that being thin will prevent you from catching Covid. Do you guys even know what you're arguing anymore?movielover said:

No one has studied it. The virus allegedly replicates in fat cells, hence the reason why people obese people were hit harder.

And again, the vaccines are better than anything else at preventing bad outcomes from an

infection.

And you know this how?

Note some African countries with very low vaxx rates also have incredibly low infection rates. Why? We know that there are low obesity rates, plenty of Vitamin D (sun), and Ivermecton for river blindness. I believe one country had less than 5,000 infections, but allegedly wealthy Africans w a western diet (fat) had a much higher infection rate.

Update: I looked it up. In 2018, there were 15.5 million cases of River Blindness. In 2016, the population of Africa was 1.215 billion. So, assuming that all the River Blindness cases were in Africa (I don't know if that's true, but I'll go with the worst case scenario), that gives an infection rate of 1.28%. That's terrible, but it does suggest that Ivermectin used to treat River Blindness isn't widespread enough to have a meaningful impact on Covid.

"The morbidity and mortality in the onchocerciasis endemic countries are lesser than those in the non-endemic ones. The community-directed onchocerciasis treatment with ivermectin is the most reasonable explanation for the decrease in morbidity and fatality rate in Africa. In areas where ivermectin is distributed to and used by the entire population, it leads to a significant reduction in mortality."

My uneducated comment: A confounding variable may be the use of Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ). It's a drug that is widely used in these same countries to prevent malaria, and a oil worker told me it was passed out like candy when he was working in Nigeria. HCQ has been shown to be effective in many countries both as a Covid treatment and as a prophylactic to reduce transmission. So the reduced mortality in Ivermectin-use countries could be due to Ivermectin, HCQ, a combination of both, or some other unknown reason. The correlation, though, is intriguing, is it not?

The US population is older and has much higher levels of chronic disease than these African countries but even adjusting for this, our track record on Covid is scandalous and shameful.

One of the first Lancet studies, possibly the fraudulent study, looked at Ivermectin alone. All of the doctors using it knew it was used in COMBINATION with other vitamins / drugs, just like the treatment for HIV. A treatment cocktail.

Gavin Newsom and his Harvard educated medical leaders couldn't even put together an efficient vaccination rollout. On top of that they had months to educate and reach out to minority communities, an unlimited budget, an educated state, and failed. Disgusting.

Gavin Newsom and his Harvard educated medical leaders couldn't even put together an efficient vaccination rollout. On top of that they had months to educate and reach out to minority communities, an unlimited budget, an educated state, and failed. Disgusting.

Because much of the world's population now has some type of immunity to SARS-CoV-2, whether from vaccination or infection, Iwasaki believes it's time to use nasal boosters instead of injected ones, in what she describes as the "prime and spike" strategy.

With so much invested in the mRNA platformmoney, time, and considerable public-health messaging to get people to trust these specific vaccinesit's a challenge to shift to a different type.

There are other questions of whether mucosal immunity against COVID-19 will be protective against disease, and whether that immunity will be enduring." That was also true of the other mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines before they were approved, but regulators relied on measuring levels of neutralizing antibodies circulating in the blood, because those could be documented more easily than levels in tissues in the mucosa. It's impossible to answer such questions without testing nasal vaccines in people in clinical trials.

while injectable vaccines are effective in protecting people from getting sick with COVID-19, they are less able to block infection. In order to put the pandemic behind us, the world will need a way to stop infections and spread of the virus. That's where a different type of vaccine, one that works at the places where the virus gets into the body, will likely prove useful.

Here, though, the U.S. is losing its edge. In September, India approved a nasal COVID-19 vaccine, and in October, China began administering an inhalable onethe world's first such vaccine against any disease. Both countries conducted their own clinical safety and efficacy tests in humans (but have not yet published the complete and latest results).

Read More: The Virus Hunters Trying to Prevent the Next Pandemic

There may be some advantages to generating a more localized, IgA-heavy responseespecially at this point in the pandemic, when blocking people from getting infected with the virus in the first place has become more of a priority. Antibody-producing cells in tissues like the mucosa tend to produce IgA antibodies that clump viruses like SARS-CoV-2 together, making them easier to neutralize en masse. An international group of scientists also reported in December 2020 that IgA antibodies dominate the first wave of people's immune response in their saliva, blood, and lungs, in an effort to block the virus from infecting more cells. In a study published in June, researchers at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) found that intranasal COVID-19 inoculation dramatically lowered the amount of virus detected in animals' respiratory tract. "We couldn't find virus in either the upper or lower respiratory tract, and we know the intranasal vaccine either prevented infection or eliminated infection within two days," says Bernard Moss, distinguished investigator at NIAID and senior author of the paper. Studies also show that people who have had COVID-19 tend to have high levels of IgA in the nose, and they are less likely to get infected if exposed to SARS-CoV-2 than people who haven't had COVID-19. That further suggests the importance of generating IgA antibodies to protect people from getting infected.

PNC Investments

Millennials are saving. Now it's time to invest.

SPONSORED BY PNC INVESTMENTS

SEE MORE

Because much of the world's population now has some type of immunity to SARS-CoV-2, whether from vaccination or infection, Iwasaki believes it's time to use nasal boosters instead of injected ones, in what she describes as the "prime and spike" strategy. Her latest results support this strategy, as she and her team reported in Science that mice given an intranasal vaccine after receiving mRNA vaccination produced higher levels of IgA antibodies in the nose and mouth than either mRNA shots or a dose of the nasal vaccine alone. The prime and spike model also produced robust immune responses, involving more immune T cells, which are more durable than antibodies.

That belief is gaining ground among immune-system experts. "We are at a different stage in the pandemic," says Stephanie Langel, instructor in the department of surgery at Duke University who developed a nasal COVID-19 vaccine based on a modified cold virus and tested it in hamsters. "Boosting people with a nasal vaccine could help to reduce things like infection and transmission, which is going to be beneficial at a time when we are all going to be spending more time indoors in poorly ventilated spaces during the winter."

CanSino Biologics' vaccine was approved by Chinese health authorities as a booster dose for this reason. It's the same vaccine as the company's injected shotwhich is about 60% effective in protecting against COVID-19 symptoms one month or more after vaccinationbut in liquid-turned-mist form that is sprayed using a nebulizer in the mouth. Both vaccines use a disabled cold virus engineered to no longer be infectious, to deliver genes coding for the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein for the immune cells to recognize and target. While the results from late-stage human studies of the mucosal vaccine aren't available, the company published early-stage data that showed people receiving the inhaled dose generated similar levels of virus-fighting antibodies as people getting the injected form of the booster. An October release summarizing later stage trials said these levels of antibodies were higher among the people receiving the inhaled dose compared to the injected one.

PNC Investments

For millennials, diversity is key to investing.

SPONSORED BY PNC INVESTMENTS

SEE MORE

Indian health officials approved a nasal vaccine for primary vaccination in two doses given through the nose, but also have not yet published the results of the human studies supporting that decision. Its nasal vaccine also uses another modified virus to deliver SARS-CoV-2 spike genes. Iran and Russia also reportedly approved nasal vaccines developed by researchers in their respective countries, but without publicly available data.

Will nasal vaccines work?

Whether these vaccines will reduce infections won't be clear until more people have taken them. Real-world analysis of how well vaccinated people can fend off infections is likely going to be the most efficient way to measure whether nasal vaccines are working.

That's because there are no widely accepted ways to document the effects that a mucosal vaccine is having on the immune system. Scientists have much less experience with mucosal vaccines, and only a handful are approved, including one for influenza and the oral polio vaccine. That makes it difficult for health authorities to measure what the vaccines are doing and to know whether they're providing protection above and beyond existing vaccines. Most people make more IgA than any other major antibody, and these levels can vary among people, so it's hard to determine a standard level, which makes tracking changes nearly impossible.

"For intranasal vaccines, we don't have good biological correlates of immunity," says Hatchett, the CEO of CEPI. "There are other questions of whether mucosal immunity against COVID-19 will be protective against disease, and whether that immunity will be enduring." That was also true of the other mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines before they were approved, but regulators relied on measuring levels of neutralizing antibodies circulating in the blood, because those could be documented more easily than levels in tissues in the mucosa. It's impossible to answer such questions without testing nasal vaccines in people in clinical trials.

That uncertainty has dissuaded biotech and pharmaceutical companies from investing in mucosal-based vaccines. While unprecedented financial support from the U.S. government fueled the development of mRNA vaccines, no such public sector resources are available for companies trying to develop a nasal vaccine. About a dozen companies have completed or are nearly finished with preliminary animal studies of various nasal vaccines, but they lack the funding needed to test their candidates in people through expensive clinical trials. "They have no financial support, no de-risking, nothing. They are in their own orbit," says Dr. Eric Topol, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute; along with Iwasaki, Topol wrote an editorial in July supporting the need for broader vaccine research, including on nasal vaccines.

If successful, nasal vaccines could also help to improve vaccination rates in lower-resource countries where vaccination with the current vaccines, which require proper storage at ultra-low temperatures, has hampered immunization rates. Increasing vaccination with a shot that significantly decreases transmission is the only way to lower spread of the virus and ultimately contain it.

"This is going to be a decades-long engagement with this virus," says Hatchett. "Having easy-to-administer intranasal vaccines to reduce transmission will help us in terms of global access to vaccines. It's way too early to talk about eradication of COVID-19, but we're never going to eradicate COVID-19 if we can't prevent transmission."

https://time.com/6226356/nasal-vaccine-covid-19-us-update/?utm_source=twitter&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=editorial&utm_term=health_covid-19&linkId=187942608&s=07

With so much invested in the mRNA platformmoney, time, and considerable public-health messaging to get people to trust these specific vaccinesit's a challenge to shift to a different type.

There are other questions of whether mucosal immunity against COVID-19 will be protective against disease, and whether that immunity will be enduring." That was also true of the other mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines before they were approved, but regulators relied on measuring levels of neutralizing antibodies circulating in the blood, because those could be documented more easily than levels in tissues in the mucosa. It's impossible to answer such questions without testing nasal vaccines in people in clinical trials.

while injectable vaccines are effective in protecting people from getting sick with COVID-19, they are less able to block infection. In order to put the pandemic behind us, the world will need a way to stop infections and spread of the virus. That's where a different type of vaccine, one that works at the places where the virus gets into the body, will likely prove useful.

Here, though, the U.S. is losing its edge. In September, India approved a nasal COVID-19 vaccine, and in October, China began administering an inhalable onethe world's first such vaccine against any disease. Both countries conducted their own clinical safety and efficacy tests in humans (but have not yet published the complete and latest results).

Read More: The Virus Hunters Trying to Prevent the Next Pandemic

There may be some advantages to generating a more localized, IgA-heavy responseespecially at this point in the pandemic, when blocking people from getting infected with the virus in the first place has become more of a priority. Antibody-producing cells in tissues like the mucosa tend to produce IgA antibodies that clump viruses like SARS-CoV-2 together, making them easier to neutralize en masse. An international group of scientists also reported in December 2020 that IgA antibodies dominate the first wave of people's immune response in their saliva, blood, and lungs, in an effort to block the virus from infecting more cells. In a study published in June, researchers at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) found that intranasal COVID-19 inoculation dramatically lowered the amount of virus detected in animals' respiratory tract. "We couldn't find virus in either the upper or lower respiratory tract, and we know the intranasal vaccine either prevented infection or eliminated infection within two days," says Bernard Moss, distinguished investigator at NIAID and senior author of the paper. Studies also show that people who have had COVID-19 tend to have high levels of IgA in the nose, and they are less likely to get infected if exposed to SARS-CoV-2 than people who haven't had COVID-19. That further suggests the importance of generating IgA antibodies to protect people from getting infected.

PNC Investments

Millennials are saving. Now it's time to invest.

SPONSORED BY PNC INVESTMENTS

SEE MORE

Because much of the world's population now has some type of immunity to SARS-CoV-2, whether from vaccination or infection, Iwasaki believes it's time to use nasal boosters instead of injected ones, in what she describes as the "prime and spike" strategy. Her latest results support this strategy, as she and her team reported in Science that mice given an intranasal vaccine after receiving mRNA vaccination produced higher levels of IgA antibodies in the nose and mouth than either mRNA shots or a dose of the nasal vaccine alone. The prime and spike model also produced robust immune responses, involving more immune T cells, which are more durable than antibodies.

That belief is gaining ground among immune-system experts. "We are at a different stage in the pandemic," says Stephanie Langel, instructor in the department of surgery at Duke University who developed a nasal COVID-19 vaccine based on a modified cold virus and tested it in hamsters. "Boosting people with a nasal vaccine could help to reduce things like infection and transmission, which is going to be beneficial at a time when we are all going to be spending more time indoors in poorly ventilated spaces during the winter."

CanSino Biologics' vaccine was approved by Chinese health authorities as a booster dose for this reason. It's the same vaccine as the company's injected shotwhich is about 60% effective in protecting against COVID-19 symptoms one month or more after vaccinationbut in liquid-turned-mist form that is sprayed using a nebulizer in the mouth. Both vaccines use a disabled cold virus engineered to no longer be infectious, to deliver genes coding for the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein for the immune cells to recognize and target. While the results from late-stage human studies of the mucosal vaccine aren't available, the company published early-stage data that showed people receiving the inhaled dose generated similar levels of virus-fighting antibodies as people getting the injected form of the booster. An October release summarizing later stage trials said these levels of antibodies were higher among the people receiving the inhaled dose compared to the injected one.

PNC Investments

For millennials, diversity is key to investing.

SPONSORED BY PNC INVESTMENTS

SEE MORE

Indian health officials approved a nasal vaccine for primary vaccination in two doses given through the nose, but also have not yet published the results of the human studies supporting that decision. Its nasal vaccine also uses another modified virus to deliver SARS-CoV-2 spike genes. Iran and Russia also reportedly approved nasal vaccines developed by researchers in their respective countries, but without publicly available data.

Will nasal vaccines work?

Whether these vaccines will reduce infections won't be clear until more people have taken them. Real-world analysis of how well vaccinated people can fend off infections is likely going to be the most efficient way to measure whether nasal vaccines are working.

That's because there are no widely accepted ways to document the effects that a mucosal vaccine is having on the immune system. Scientists have much less experience with mucosal vaccines, and only a handful are approved, including one for influenza and the oral polio vaccine. That makes it difficult for health authorities to measure what the vaccines are doing and to know whether they're providing protection above and beyond existing vaccines. Most people make more IgA than any other major antibody, and these levels can vary among people, so it's hard to determine a standard level, which makes tracking changes nearly impossible.

"For intranasal vaccines, we don't have good biological correlates of immunity," says Hatchett, the CEO of CEPI. "There are other questions of whether mucosal immunity against COVID-19 will be protective against disease, and whether that immunity will be enduring." That was also true of the other mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines before they were approved, but regulators relied on measuring levels of neutralizing antibodies circulating in the blood, because those could be documented more easily than levels in tissues in the mucosa. It's impossible to answer such questions without testing nasal vaccines in people in clinical trials.

That uncertainty has dissuaded biotech and pharmaceutical companies from investing in mucosal-based vaccines. While unprecedented financial support from the U.S. government fueled the development of mRNA vaccines, no such public sector resources are available for companies trying to develop a nasal vaccine. About a dozen companies have completed or are nearly finished with preliminary animal studies of various nasal vaccines, but they lack the funding needed to test their candidates in people through expensive clinical trials. "They have no financial support, no de-risking, nothing. They are in their own orbit," says Dr. Eric Topol, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute; along with Iwasaki, Topol wrote an editorial in July supporting the need for broader vaccine research, including on nasal vaccines.

If successful, nasal vaccines could also help to improve vaccination rates in lower-resource countries where vaccination with the current vaccines, which require proper storage at ultra-low temperatures, has hampered immunization rates. Increasing vaccination with a shot that significantly decreases transmission is the only way to lower spread of the virus and ultimately contain it.

"This is going to be a decades-long engagement with this virus," says Hatchett. "Having easy-to-administer intranasal vaccines to reduce transmission will help us in terms of global access to vaccines. It's way too early to talk about eradication of COVID-19, but we're never going to eradicate COVID-19 if we can't prevent transmission."

https://time.com/6226356/nasal-vaccine-covid-19-us-update/?utm_source=twitter&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=editorial&utm_term=health_covid-19&linkId=187942608&s=07

Stillbirths pic.twitter.com/2BgthiOxFO

— David Wolfe (@DavidWolfe) November 5, 2022

What is the source?

Your chart is claiming that before 2005 there were 25 or fewer miscarriages/stillbirths per year? I find that hard to believe and makes me doubt the rest of the data. The chart needs some further explaining as to what is being shown. Frankly 4,000 or more doesn't seem outrageous if you're talking about the US or other large country. My mother had 4 miscarriages/stillbirths back in the 1950s. I was born 6 weeks premature and was touch and go for a while.Cal88 said:Stillbirths pic.twitter.com/2BgthiOxFO

— David Wolfe (@DavidWolfe) November 5, 2022

I dug through the replies and it's based on vaers data... The CDC has warnings about drawing inferences on vaers data for a reason... But that won't stop the anti-vax crowd.

Miscarriages are *very* common. 15-20% of pregnancies end in miscarriage. The graph makes zero sense without additional context since the numbers are way off as you note.

And a quick review of literature shows ample evidence that vaccination does not increase risk of miscarriage:

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMc2114466

https://www.bmj.com/content/378/bmj-2022-071416

https://www.bmj.com/content/378/bmj-2021-069741

What does seem to cause an increased risk of negative outcomes is getting covid:

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7047e1.htm

Miscarriages are *very* common. 15-20% of pregnancies end in miscarriage. The graph makes zero sense without additional context since the numbers are way off as you note.

And a quick review of literature shows ample evidence that vaccination does not increase risk of miscarriage:

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMc2114466

https://www.bmj.com/content/378/bmj-2022-071416

https://www.bmj.com/content/378/bmj-2021-069741

What does seem to cause an increased risk of negative outcomes is getting covid:

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7047e1.htm

movielover said:

What is the source?

The source is openvaers.com, which collates data from VAERS. I guess the reports in years before covid are related to flu shots. I agree with the critics above, it`s still raw data.

One troubling trend is that newborn babies have been dying at a much higher rates than normal, but those deaths have been wrongly labelled as stillbirths, in order to stave off any formal coronary investigation process. Average mortality rates for newborns have doubled in Scotland, but could be much higher yet, due to the aforementioned fact:

I`m going to share my personal experience here, a former co-worker who was a 35yo fit woman, thin avid cyclist and crunchy health nut died from a brain aneurysm overnight the Sunday after getting her first vax on Friday back in March 21, she was literally first in line in her age group.

One very troubling aspect of her death is that it was never reported in VAERS, and her parents refuse to entertain the notion that her death might be related to the mRNA shot, as did most of her coworkers.

Well then that explains it. The public wasn't posting "cases" to VAERS until Covid increased awareness of VAERS's existence. Most likely miscarriages and stillbirths weren't being reported much in the past, so the numbers before Covid were very unrepresentative.Cal88 said:movielover said:

What is the source?

The source is openvaers.com, which collates data from VAERS. I guess the reports in years before covid are related to flu shots. I agree with the critics above, it`s still raw data.

One troubling trend is that newborn babies have been dying at a much higher rates than normal, but those deaths have been wrongly labelled as stillbirths, in order to stave off any formal coronary investigation process. Average mortality rates for newborns have doubled in Scotland, but could be much higher yet, due to the aforementioned fact:

I`m going to share my personal experience here, a former co-worker who was a 35yo fit woman, thin avid cyclist and crunchy health nut died from a brain aneurysm overnight the Sunday after getting her first vax on Friday back in March 21, she was literally first in line in her age group.

One very troubling aspect of her death is that it was never reported in VAERS, and her parents refuse to entertain the notion that her death might be related to the mRNA shot, as did most of her coworkers.

It's probably best not to confuse RWNJs with facts. Facts - even simple and easily verified ones - tend make their tiny little brains hurt.

Repeat after me.

1) Every side effect of the vaccine is normal.

2) The massive amount of side effects reported in VAERS is normal because VAERS can't be trusted because it was hardly used prior.

3) If overwhelming evidence worldwide causes the CDC to acknowledge a side effect of covid vaccines, such as "mild" myocarditis, it is no reason to be alarmed because, surely enough, the disease it attempts to prevent causes more of that side effect than the vaccine itself.

4) Only people with tin-foil hats disagree with points 1-3.

1) Every side effect of the vaccine is normal.

2) The massive amount of side effects reported in VAERS is normal because VAERS can't be trusted because it was hardly used prior.

3) If overwhelming evidence worldwide causes the CDC to acknowledge a side effect of covid vaccines, such as "mild" myocarditis, it is no reason to be alarmed because, surely enough, the disease it attempts to prevent causes more of that side effect than the vaccine itself.

4) Only people with tin-foil hats disagree with points 1-3.

Is point 4 really necessary? Does insulting people advance the conversation in any way?oski003 said:

Repeat after me.

1) Every side effect of the vaccine is normal.

2) The massive amount of side effects reported in VAERS is normal because VAERS can't be trusted because it was hardly used prior.

3) If overwhelming evidence worldwide causes the CDC to acknowledge a side effect of covid vaccines, such as "mild" myocarditis, it is no reason to be alarmed because, surely enough, the disease it attempts to prevent causes more of that side effect than the vaccine itself.

4) Only people with tin-foil hats disagree with points 1-3.

tequila4kapp said:Is point 4 really necessary? Does insulting people advance the conversation in any way?oski003 said:

Repeat after me.

1) Every side effect of the vaccine is normal.

2) The massive amount of side effects reported in VAERS is normal because VAERS can't be trusted because it was hardly used prior.

3) If overwhelming evidence worldwide causes the CDC to acknowledge a side effect of covid vaccines, such as "mild" myocarditis, it is no reason to be alarmed because, surely enough, the disease it attempts to prevent causes more of that side effect than the vaccine itself.

4) Only people with tin-foil hats disagree with points 1-3.

I am being sarcastic!

Lots of sketchy and troubling issues around this vaxx. I believe Dr. Campbell above states that the stillbirths in Scotland were just assumed to not be vaxx related.

So many non-standard events occurring. Dissent censored, doctors being censored, doctors in California being threatened with having their licenses revoked if they suggest non-approved Covid treatments, teachers associations setting medical policies, fraudulent Lancet study about the effectiveness of a therapeutic (papers like this go through a detailed, multi-step verification), the CDC lying about the vaxx stopping the transmission of the virus, vaxx participants "control group" subsequently vaccinated, etc.

So many non-standard events occurring. Dissent censored, doctors being censored, doctors in California being threatened with having their licenses revoked if they suggest non-approved Covid treatments, teachers associations setting medical policies, fraudulent Lancet study about the effectiveness of a therapeutic (papers like this go through a detailed, multi-step verification), the CDC lying about the vaxx stopping the transmission of the virus, vaxx participants "control group" subsequently vaccinated, etc.

Some people have been critical of my reporting choices lately. That's ok!! But I have a critique of my own.

— Emily Kopp (@emilyakopp) November 7, 2022

(Thank you @theabridgedzach & team for putting together an amazing video!)https://t.co/4Zs37nvW9v pic.twitter.com/eyavNJGwOA

Yeah, that's absolutely right. Ironically, Cal88 (in his attempt to fearmonger) has done a great job of demonstrating why VAERS isn't reliable. Does anyone really believe the number of stillbirths/miscarriages really went up 3000x in 2020? That the rate of such was so low prior to that? No, I don't think so.oski003 said:

2) The massive amount of side effects reported in VAERS is normal because VAERS can't be trusted because it was hardly used prior.

That number only jumps because a whole lot of people became more aware of VAERS in 2020. There was a new vaccine that a bunch of people took at the same time (with multiple doses) and a massive publicity campaign around them. The primary reason you're seeing so many new reports in VAERS is because of response bias.

Now, that doesn't mean that the vaccines lack side effects and that we might need to learn more about them. But the VOLUME of reports doesn't mean anything, if you're comparing to years past.

sycasey said:Yeah, that's absolutely right. Ironically, Cal88 (in his attempt to fearmonger) has done a great job of demonstrating why VAERS isn't reliable. Does anyone really believe the number of stillbirths/miscarriages really went up 3000x in 2020? That the rate of such was so low prior to that? No, I don't think so.oski003 said:

2) The massive amount of side effects reported in VAERS is normal because VAERS can't be trusted because it was hardly used prior.

That number only jumps because a whole lot of people became more aware of VAERS in 2020. There was a new vaccine that a bunch of people took at the same time (with multiple doses) and a massive publicity campaign around them. The primary reason you're seeing so many new reports in VAERS is because of response bias.

Now, that doesn't mean that the vaccines lack side effects and that we might need to learn more about them. But the VOLUME of reports doesn't mean anything, if you're comparing to years past.

The United States was one of the last developed countries in the world to recognize that the vaccines caused myocarditis. Other European countries banned Moderna for under 30 males before the U.S. acknowledged a link. When it was finally acknowledged, the term "mild myocarditis" was invented by the American Medical Industry. I almost fell out of my chair. The primary reason side effects are being deflected is called Big Pharma bias.

sycasey said:Yeah, that's absolutely right. Ironically, Cal88 (in his attempt to fearmonger) has done a great job of demonstrating why VAERS isn't reliable. Does anyone really believe the number of stillbirths/miscarriages really went up 3000x in 2020? That the rate of such was so low prior to that? No, I don't think so.oski003 said:

2) The massive amount of side effects reported in VAERS is normal because VAERS can't be trusted because it was hardly used prior.

That number only jumps because a whole lot of people became more aware of VAERS in 2020. There was a new vaccine that a bunch of people took at the same time (with multiple doses) and a massive publicity campaign around them. The primary reason you're seeing so many new reports in VAERS is because of response bias.

Now, that doesn't mean that the vaccines lack side effects and that we might need to learn more about them. But the VOLUME of reports doesn't mean anything, if you're comparing to years past.

Do you think that the skyrocketing rate of heart injuries among professional athletes right after the vax rollout also is a manifestation of some kind of a cognitive bias?

Do you also have a chart for that or is it just anecdotes?Cal88 said:sycasey said:Yeah, that's absolutely right. Ironically, Cal88 (in his attempt to fearmonger) has done a great job of demonstrating why VAERS isn't reliable. Does anyone really believe the number of stillbirths/miscarriages really went up 3000x in 2020? That the rate of such was so low prior to that? No, I don't think so.oski003 said:

2) The massive amount of side effects reported in VAERS is normal because VAERS can't be trusted because it was hardly used prior.

That number only jumps because a whole lot of people became more aware of VAERS in 2020. There was a new vaccine that a bunch of people took at the same time (with multiple doses) and a massive publicity campaign around them. The primary reason you're seeing so many new reports in VAERS is because of response bias.

Now, that doesn't mean that the vaccines lack side effects and that we might need to learn more about them. But the VOLUME of reports doesn't mean anything, if you're comparing to years past.

Do you think that the skyrocketing rate of heart injuries among professional athletes right after the vax rollout also is a manifestation of some kind of a cognitive bias?

sycasey said:Do you also have a chart for that or is it just anecdotes?Cal88 said:sycasey said:Yeah, that's absolutely right. Ironically, Cal88 (in his attempt to fearmonger) has done a great job of demonstrating why VAERS isn't reliable. Does anyone really believe the number of stillbirths/miscarriages really went up 3000x in 2020? That the rate of such was so low prior to that? No, I don't think so.oski003 said:

2) The massive amount of side effects reported in VAERS is normal because VAERS can't be trusted because it was hardly used prior.

That number only jumps because a whole lot of people became more aware of VAERS in 2020. There was a new vaccine that a bunch of people took at the same time (with multiple doses) and a massive publicity campaign around them. The primary reason you're seeing so many new reports in VAERS is because of response bias.

Now, that doesn't mean that the vaccines lack side effects and that we might need to learn more about them. But the VOLUME of reports doesn't mean anything, if you're comparing to years past.

Do you think that the skyrocketing rate of heart injuries among professional athletes right after the vax rollout also is a manifestation of some kind of a cognitive bias?

Hank Aaron died within days of receiving his covid shot. He was 86, died in his sleep, and it was determined to be death from natural causes. Who is going to chart that?

An 86 year old man dying in his sleep? Why would anyone think that was unusual?oski003 said:sycasey said:Do you also have a chart for that or is it just anecdotes?Cal88 said:sycasey said:Yeah, that's absolutely right. Ironically, Cal88 (in his attempt to fearmonger) has done a great job of demonstrating why VAERS isn't reliable. Does anyone really believe the number of stillbirths/miscarriages really went up 3000x in 2020? That the rate of such was so low prior to that? No, I don't think so.oski003 said:

2) The massive amount of side effects reported in VAERS is normal because VAERS can't be trusted because it was hardly used prior.

That number only jumps because a whole lot of people became more aware of VAERS in 2020. There was a new vaccine that a bunch of people took at the same time (with multiple doses) and a massive publicity campaign around them. The primary reason you're seeing so many new reports in VAERS is because of response bias.

Now, that doesn't mean that the vaccines lack side effects and that we might need to learn more about them. But the VOLUME of reports doesn't mean anything, if you're comparing to years past.

Do you think that the skyrocketing rate of heart injuries among professional athletes right after the vax rollout also is a manifestation of some kind of a cognitive bias?

Hank Aaron died within days of receiving his covid shot. He was 86, died in his sleep, and it was determined to be death from natural causes. Who is going to chart that?

sycasey said:An 86 year old man dying in his sleep? Why would anyone think that was unusual?oski003 said:sycasey said:Do you also have a chart for that or is it just anecdotes?Cal88 said:sycasey said:Yeah, that's absolutely right. Ironically, Cal88 (in his attempt to fearmonger) has done a great job of demonstrating why VAERS isn't reliable. Does anyone really believe the number of stillbirths/miscarriages really went up 3000x in 2020? That the rate of such was so low prior to that? No, I don't think so.oski003 said:

2) The massive amount of side effects reported in VAERS is normal because VAERS can't be trusted because it was hardly used prior.

That number only jumps because a whole lot of people became more aware of VAERS in 2020. There was a new vaccine that a bunch of people took at the same time (with multiple doses) and a massive publicity campaign around them. The primary reason you're seeing so many new reports in VAERS is because of response bias.

Now, that doesn't mean that the vaccines lack side effects and that we might need to learn more about them. But the VOLUME of reports doesn't mean anything, if you're comparing to years past.

Do you think that the skyrocketing rate of heart injuries among professional athletes right after the vax rollout also is a manifestation of some kind of a cognitive bias?

Hank Aaron died within days of receiving his covid shot. He was 86, died in his sleep, and it was determined to be death from natural causes. Who is going to chart that?

It is so easy to disregard the causation, right? If they are old, it is natural. If they are young, they probably had covid at some point or would have had covid at some point and would have been ill regardless.

If they didn`t have the vaccine, they would have probably died harder...

If causation could actually be demonstrated, then that would be something. Your statement did not demonstrate it. It's the basic definition of "correlation is not causation."oski003 said:sycasey said:An 86 year old man dying in his sleep? Why would anyone think that was unusual?oski003 said:sycasey said:Do you also have a chart for that or is it just anecdotes?Cal88 said:sycasey said:Yeah, that's absolutely right. Ironically, Cal88 (in his attempt to fearmonger) has done a great job of demonstrating why VAERS isn't reliable. Does anyone really believe the number of stillbirths/miscarriages really went up 3000x in 2020? That the rate of such was so low prior to that? No, I don't think so.oski003 said:

2) The massive amount of side effects reported in VAERS is normal because VAERS can't be trusted because it was hardly used prior.

That number only jumps because a whole lot of people became more aware of VAERS in 2020. There was a new vaccine that a bunch of people took at the same time (with multiple doses) and a massive publicity campaign around them. The primary reason you're seeing so many new reports in VAERS is because of response bias.

Now, that doesn't mean that the vaccines lack side effects and that we might need to learn more about them. But the VOLUME of reports doesn't mean anything, if you're comparing to years past.

Do you think that the skyrocketing rate of heart injuries among professional athletes right after the vax rollout also is a manifestation of some kind of a cognitive bias?

Hank Aaron died within days of receiving his covid shot. He was 86, died in his sleep, and it was determined to be death from natural causes. Who is going to chart that?

It is so easy to disregard the causation, right? If they are old, it is natural. If they are young, they probably had covid at some point or would have had covid at some point and would have been ill regardless.

sycasey said:If causation could actually be demonstrated, then that would be something. Your statement did not demonstrate it. It's the basic definition of "correlation is not causation."oski003 said:sycasey said:An 86 year old man dying in his sleep? Why would anyone think that was unusual?oski003 said:sycasey said:Do you also have a chart for that or is it just anecdotes?Cal88 said:sycasey said:Yeah, that's absolutely right. Ironically, Cal88 (in his attempt to fearmonger) has done a great job of demonstrating why VAERS isn't reliable. Does anyone really believe the number of stillbirths/miscarriages really went up 3000x in 2020? That the rate of such was so low prior to that? No, I don't think so.oski003 said:

2) The massive amount of side effects reported in VAERS is normal because VAERS can't be trusted because it was hardly used prior.

That number only jumps because a whole lot of people became more aware of VAERS in 2020. There was a new vaccine that a bunch of people took at the same time (with multiple doses) and a massive publicity campaign around them. The primary reason you're seeing so many new reports in VAERS is because of response bias.

Now, that doesn't mean that the vaccines lack side effects and that we might need to learn more about them. But the VOLUME of reports doesn't mean anything, if you're comparing to years past.

Do you think that the skyrocketing rate of heart injuries among professional athletes right after the vax rollout also is a manifestation of some kind of a cognitive bias?

Hank Aaron died within days of receiving his covid shot. He was 86, died in his sleep, and it was determined to be death from natural causes. Who is going to chart that?

It is so easy to disregard the causation, right? If they are old, it is natural. If they are young, they probably had covid at some point or would have had covid at some point and would have been ill regardless.

If someone has a heart attack or stroke with covid, covid caused it. If someone has such within days of getting the vaccine, it is assumed to be natural causes. No further investigation necessary!

Featured Stories

See All

Cal Clinches 'Huge' Conference Win Against SMU

by Ian Firstenberg

The Rodcast: We Swept Stanford

by Rod Benson

Cal aims to keep rolling vs. SMU's 'lot of weapons'

by Joaquin Ruiz